“I’m doing the starving artist thing,” I told someone recently. Ah. Something clicked in the lady’s eyes, an understanding of my situation. A woman in her mid-twenties with a college degree working multiple part-time jobs doesn’t make sense—unless she has a reason. Unless she’s a starving artist trying to make it as a writer.

While I do think I fit a socially-accepted definition of the term—someone “who sacrifices material well-being in order to focus on their artwork”—I’m in no way starving. I quit a full-time job as a caseworker to work in food service, with the hopes of having time and mental energy to focus on my writing career. I’m lucky to say that, unless an apocalypse happens, I will never starve. I will never be homeless, and I won’t even have to wonder if my utilities are going to get turned off. That’s because I’m privileged enough to have a loving family and friends with the means to help me if I need it. Not to say this is a Gilmore Girls situation where my extended family has set me up with a cushy trust fund that will fund my flailings, as we find out Rory will have when she turns 25 (S1:E18). But if worst comes to worst, I can always move back into my childhood bedroom or ask my mom for twenty bucks to buy dinner. Privilege is a word people have been trying to avoid lately, ignoring the fact that it doesn’t always mean trust fund or nepo baby.

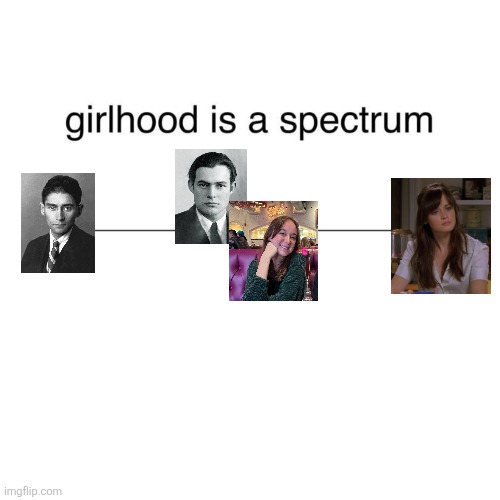

As a white woman with a middle-class background, I do have a limited perspective. But the way I see it, there are three kinds of “starving artists,” and they run a wide spectrum. My list focuses mainly on writers, but I wouldn’t be surprised if visual artists recognized these tropes, too:

- I Might Actually Starve: I’m thinking of Casey from Lily King’s Writers and Lovers. At the novel’s opening, she’s drowning in debt to the point of threatened wage garnishment. She can only go to the doctor because she found out her serving job magically has insurance, but she’s under the wire to fit it all in when she gets fired. Her family is dysfunctional to the point of legal implications, and the only reason she has her box of a room is because her brother is in a situationship with the guy who owns the house. That’s the total of her safety net, and this level of need is beyond the comprehension of her old friends, one of whom can’t understand why Casey can’t afford to come to her destination wedding.

- Paris Ex-Pat: I would put myself in this category. When I was recently on a three-month-long job hunt, my family helped me cover what I couldn’t. I relate a lot to Ernest Hemingway, as he describes himself in A Moveable Feast. In a chapter titled “Hunger Was Good Discipline,” he’s young, living in Paris, and trying to make ends meet by writing short stories:

You God damn complainer. You dirty phony saint and martyr, I said to myself. You quit journalism of your own accord. You have credit and Sylvia would have loaned you money. She has plenty of times. Sure. And then the next thing you would be compromising on something else.

I originally read this book years ago, and when I came across this quote again, I was shocked at the similarities between a young Hemingway and me. During my job search, I kept thinking about the jobs I’ve willingly given up, like my brief stint as a reporter. I’d often try to console myself with the reminder that I have credit and people happy to help me when they could. I can try to scrimp and save and subsist on ramen noodles, and maybe sometimes that’s the responsible thing to do. At the end of the day, though, I’m lucky it’s not my only option. - Rory Gilmore: In her defense, I don’t recall Rory ever trying to say that she’s a starving artist. But I do recall, when the limited reboot A Year in the Life debuted, seeing Rory in her 30s and wondering how the hell she was paying her bills and affording to jet back and forth between Stars Hollow and London to hook up with her college ex. At one point, she claims to be broke, but what happened to the trust fund? She’s writing articles here and there, but still struggling to find fulfillment and true success. “This is my time,” she says in episode one, “to be rootless and just see where life takes me and travel wherever there’s a story to write.” Only her grandmother seems to be concerned about this plan through the course of the show. “Why is everyone treating this like it’s a normal rite of passage?” asks the woman who once let Rory live in her pool house.

Honorable mention goes to Franz Kafka’s short story “A Hunger Artist,” where the term is literal. The man that the story centers around makes his way by actually starving himself for audiences. It’s a compulsion for him:

“Because I had to fast. I can’t do anything else,” said the hunger artist. “Just look at you,” said the supervisor, “why can’t you do anything else?” “Because,” said the hunger artist, lifting his head a little and, with his lips pursed as if for a kiss, speaking right into the supervisor’s ear so that he wouldn’t miss anything, “because I couldn’t find a food which I enjoyed…believe me, I would not have made a spectacle of myself and would have eaten to my heart’s content, like you and everyone else.”

My answer is the same. I don’t want to get an office job, and I haven’t kept a nine-to-five for more than a couple of years, tops. There’s nothing wrong with those jobs, and sometimes, when I’m wondering if I’m making enough tips at work, I think about doing that again, or becoming a teacher, like everyone assumed I would when I told them I was studying English. But those aren’t foods I enjoy, nothing that will sustain me. So I know what he means, this hunger artist. He couldn’t find something to fill him up inside, but I have. Even if it’s hard now, even if it looks strange, and people don’t understand or believe that I really could be doing something else if I wanted to. The short story goes on:

Sometimes he overcame his weakness and sang during the time they were observing, for as long as he could keep it up, to show people how unjust their suspicions about him were. But that was little help. For then they just wondered among themselves about his skill at being able to eat even while singing.

At the end of the day, maybe starving artist is just an explanation, a palatable excuse for not having life figured out yet. The first time I watched A Year in the Life, I judged Rory. I grew up wanting to be like her, and I was like her, up to a point—a precocious reader who talked too fast and wrapped everything in a reference to pop culture. I was in college when a Rory in her early 30s had less figured out than she did when she was going to prep school. But the closer I get to that age, the more I understand it. Not having everything worked out doesn’t mean you’re not trying. I’ve been thinking about that chapter title of Hemingway’s a lot recently: “Hunger Was Good Discipline.” Maybe some people, myself included, need a tiny manifestation of an internal hunger to stay committed.